Talitha Balan, Visiting Practitioner in Academic Support, Central Saint Martins

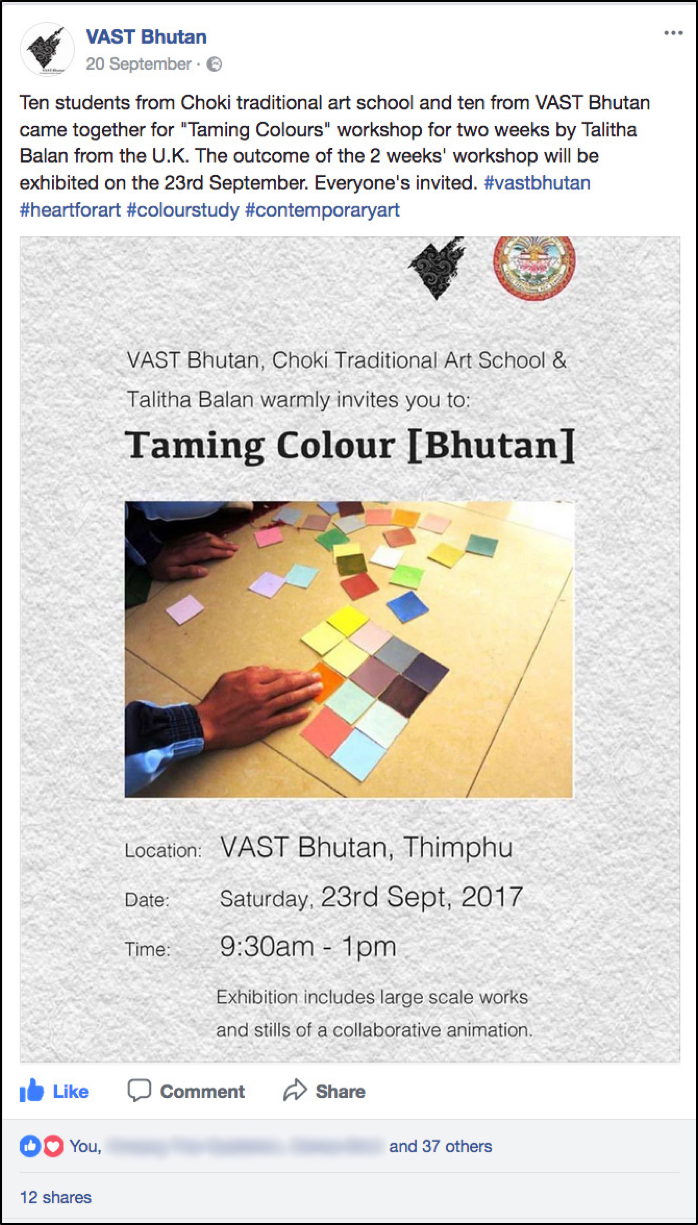

This article adopts the format of a research paper and photo essay, documenting a painting workshop in the Himalayan kingdom of Bhutan, carried out by an art and design lecturer of mixed Indian, South East Asian and European heritage. It describes the visual methodologies that informed the design of a colour study workshop, the outcomes of which were showcased at the exhibition Taming Colour in Bhutan (23 September, 2017). The images used in this article include photographs taken and shared on social media platforms by participants and attendees. Born out of complexities arising in Bhutan over the past decade that are related to artefact production, including the availability of acrylic paint and smartphones, the article considers perspective of a ‘knowledge gap’ in traditional Bhutanese painting to create transcultural, technical encounters with a focus on colour harmonisation and 3D rendering skills.

Bhutan; Choki Traditional Art School; VAST Bhutan; Bhutanese contemporary art; cross-cultural education; visual research methods; photo essay; thangka

All photos are by the author unless otherwise credited.

Located east of the Himalayan mountain range and much like regional neighbour Tibet, Bhutan is one of the last remaining nations that uphold sacred Buddhist teaching and practices. This extends to arts and crafts, including an artistic practice upheld in Buddhist teaching, the painting method ‘thangka’.

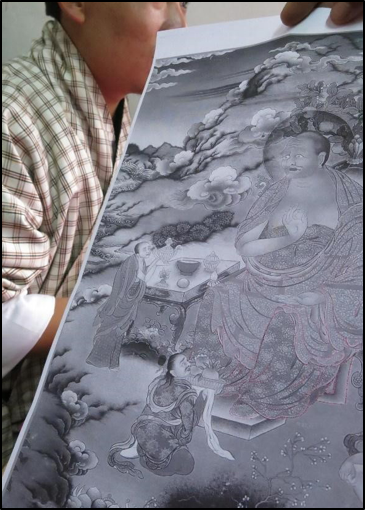

Thangka (as shown in Figure 1) is a traditional painting art form within the teachings of Buddhism that has three main types: didactic, narrative and meditative (Karma and Wangdi, 2016, p.39). Traditional Bhutanese paintings may feature a deity or a landscape scene that illustrates religious history or instruction. It is an art form practiced predominantly within the Himalayan region and includes countries such as Tibet, though this article focuses on Bhutanese thangka.

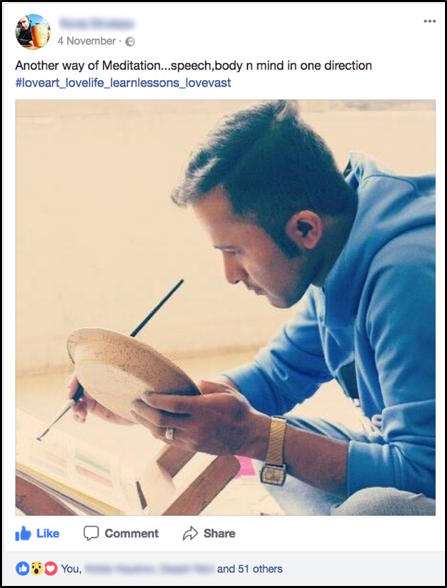

Similar to other traditional painting practices such as Ch’an or Zen Buddhism, in thangka, a sense of form, rhythmic feeling and relaxed attentiveness are used. This mental and physical process achieves ‘inward automatism’, whereby brushwork flows effortlessly in a disciplined manner. Buddhist monks, for example, worked with the brush as an aid to meditative internalization (Itten, 1970, p.49).

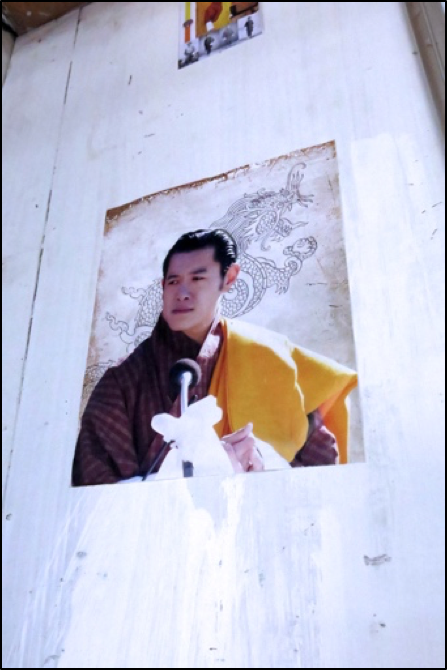

For centuries, to facilitate meditation, thangka are comparatively predetermined by using templates. The same template, for example featuring Guru Dragpo (Figure 2) may be replicated by hundreds of traditional painters. Traditional Bhutanese art had ‘strong didactic intentions […] to convey the profound teachings of Buddha’ foremost, other issues such as ‘artistic creativity, stylistic distinctions and the identity of the artists [were] not important in traditional Bhutanese painting’ (Karma and Wangdi, 2016, p.12).

In the past, thangka was almost solely practiced by Buddhist monks, but a transition occurred in Bhutan between approximately 1960 and 1980, when monks no longer painted solely for meditation. Devout followers and citizens are ‘commissioned by monks or common laity’ (Karma and Wangdi, 2016, p.38) to cultivate painting skills and create thangka for the karmic rewards prescribed in Buddhist teaching. Additionally, traditional painting skills extended a means of earning income for families, by selling the artefact, or decorating architectural exteriors or interiors (Altmann, 2016).

Since this transition in painting practice from monk to citizen, the role and audience of traditional painting has changed. Local and international audience perception has become a consideration due to the potential capacity for people to earn a living. When I first visited Bhutan, I arrived approximately 50 years after this transition, witnessing how modernity has changed traditional artistic practices in Bhutan. This transition is the historical event that lies at the root of the following article.

Students found it a challenge to create non-traditional art forms and Choki School invited me to run another workshop with students as a way of introducing elements of outsider ‘taste’ that would expand the audience and enhance appeal of the non-traditional artworks they produced, sold through their shop onsite and online to boost funding.

The subsequent workshop I designed developed insights from my experiences teaching at the Srishti Institute which, combined with my mixed Indian, South East Asian and European heritage, resulted in an adaptation of teaching skills in cross-cultural learning. It was pedagogically useful to bypass linguistically focused engagement when, for example, the spoken language used by Bhutanese participants relating to workshop learning outcomes seemed to prioritise other non-traditional forms of art over the Bhutanese style. This was problematic as adapting traditional and non-traditional forms to create outcomes was a priority during the workshop and I had to sensitively apply ‘an aesthetic of openness towards otherness’ (Wilson, 1998, p.351) in order to design a disciplinary-inclusive workshop.

I was able to grapple underlying complexities facing Choki School related to financial pressures and maintaining a traditional outlook though I faced several difficulties when designing this workshop due to differing institutional evaluative criteria.

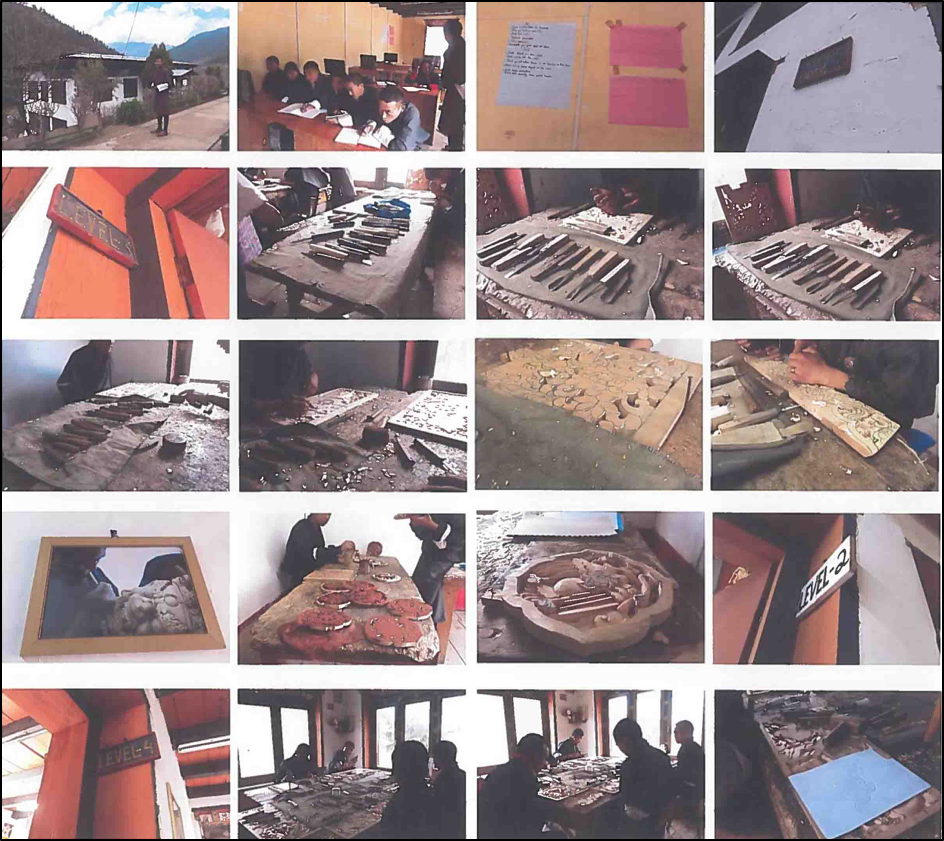

For example, in UK higher education arts curricula explorative material processes should be documented, but in traditional Himalayan art and craft schools material processes are less significant than cultural artefacts in predetermined formats such as thangka. The workshop aimed to discover cross-cultural learning and teaching strategies and engage Bhutanese painters in emerging alternative ideas, whilst also creating resources for peers that can be used in classes populated by people from unknown and mixed cultural backgrounds.

The key point was to help traditional painters consider outsider tastes. Through appealing to outsider taste, work created could reach an even wider audience by greater circulation, a poignant situation for artists and others in Bhutan, which has been relatively closed to the rest of the world for centuries. Since limited tourism was introduced in Bhutan in 1974, the government levies a costly tourist visa, charging US$250 a day to most foreign visitors.

Although traditional visual mediation techniques such as thangka are still practised, it became increasingly important during the research to adapt workshop participants’ established skills to a range of possibilities, using digital and online technologies to reach wider audiences.

In order to design learning outcomes that helped participants to enhance the appeal of artworks created and circulated with a digital emphasis, the research uncovered another significant change that has affected thangka practice, the introduction of acrylic paint.

Previously, natural pigment and mineral colours predominated. Published historical reference indicating when acrylic paint was first introduced in Bhutan is scarce, however, conversations with thangka masters indicates that they started using it in their works in the late 1990s to early 2000s, almost five decades after its invention in the United States in the late 1940s. Previously in Bhutanese thangka, natural minerals were laboriously sourced, extracted and applied. At Choki School acrylic paints are easily sourced and applied, however, the process of harmonising colour is complex and challenging. Although the School has a strictly traditional focus, the painting programme is focused on speed and production and there is now less time to develop painting skills for karmic rewards, as devout followers and monks used to do in the past.

This impacts sale as it is does not give the appearance of what thangka, painted in the past with mineral colours, looks like. This is pertinent as the school seeks to boost funding by the sale of artefacts with an authentic appearance.

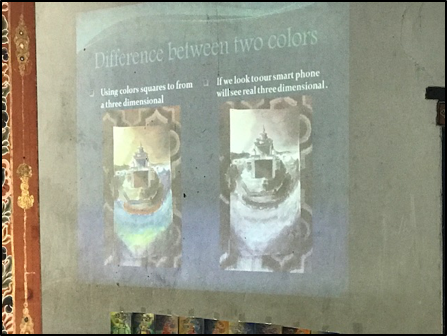

The Swiss painter Johannes Itten, who taught at the Bauhaus, developed exercises for creating three-dimensionality in images. He argued that most of us are born with the ability to separate colours, but that painters must take it further and use each colour to its correct tonal value. For example, a lighter foreground, medium toned mid-ground and dark background, are pivotal to creating spatial depth. Itten’s exercises delve deeper into tonal differentiation, into what he terms ‘organization of planes’ (Itten, 1970, p.42).

Tonal light-dark proportions affect overall harmony within pictorial compositions and influence how an audience perceives spatial depth. Attaining ‘an effect of physical reality’, ‘concreteness’ and audience perception is now an important consideration in Bhutan. Identifying these problems of poor colour harmonisation skills led to the inclusion of Itten’s techniques in the workshop.

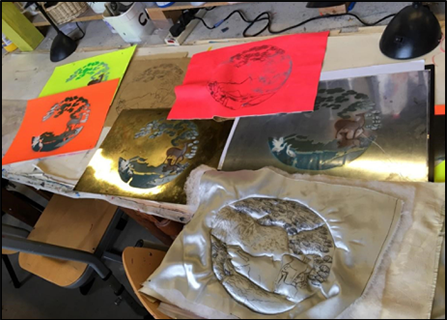

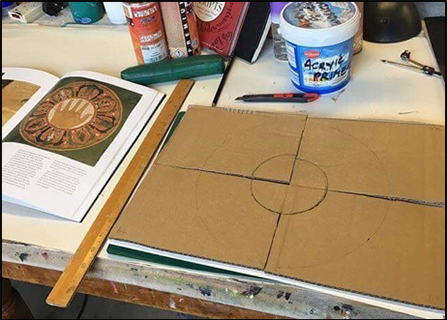

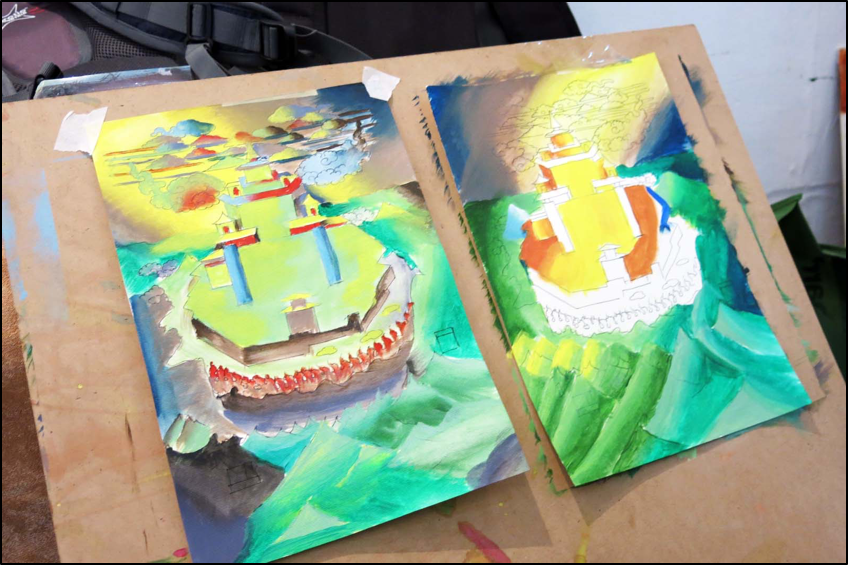

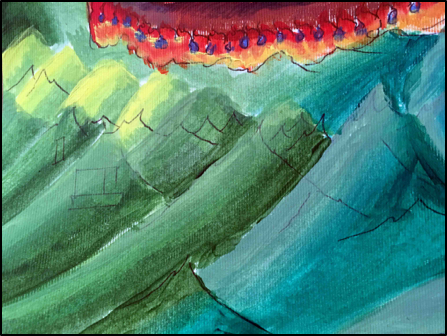

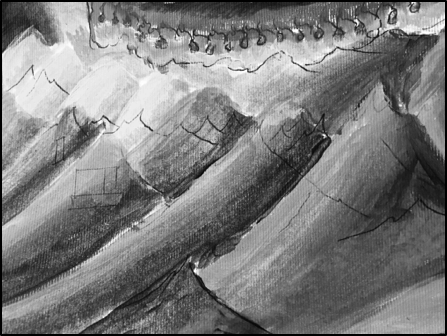

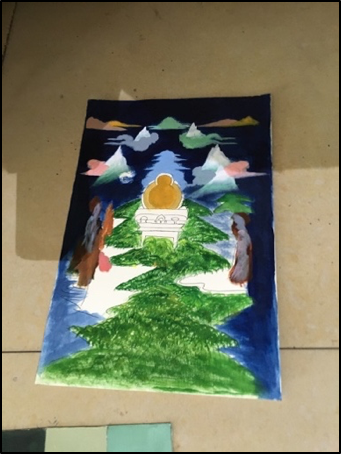

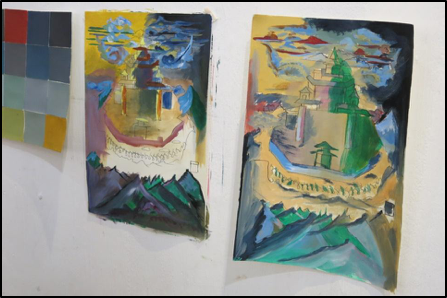

My art practice helped me gain further first-hand experience of thangka practice. By creating works using some pictorial elements of a Bhutanese thangka. I reflected on aspects of the traditional Bhutanese painting curriculum and made ‘researching your own practice a key element of educational enquiry in creative practice’ by ‘merging theory and practice […] to implement action’ (Orr and McDougall, 2014, p.175).

I took the works I created, with these material similarities and dissimilarities to the traditional painting curriculum, to Bhutan. They helped build a common context by illustrating and making recognisable ideas I wished to develop through dialogue with thangka masters, workshop commissioners and participants. These experimental and awareness of the available resources further clarified research aims.

In Bhutan, the Choki School principal introduced me to Voluntary Artist’s Studio Thimphu (VAST Bhutan) the country’s most prominent non-exclusively traditional art organisation.

They organised my entry visa and provided a workshop space in the country’s capital city, Thimphu. VAST Bhutan members comprise of local Bhutanese artists who’ve had local traditional and/or non-traditional art education in surrounding countries. Some have had no formal training whatsoever and are self-taught.

‘Technique’ was the focus of the workshop, which aimed to explore elements that are less established in Bhutanese painting. A brief was clarified, to help participants create work that appears ‘less flat’ and ‘more 3D’ through learning about colour harmonisation.

As this article discusses how spoken language can be supplemented or enhanced by visual techniques in order to be disciplinary and culturally inclusive (McDonald, 2004) so too did the research adopt a more visual form.

‘Shooting script’ methodology

The resultant shooting script informed subsequent research sub questions and these were aligned to workshop learning outcomes/activities and other shooting scripts to produce visual data for further evaluation (Table 1).

| Activity | Description | Learning outcome (LO) | Template (T) |

|---|---|---|---|

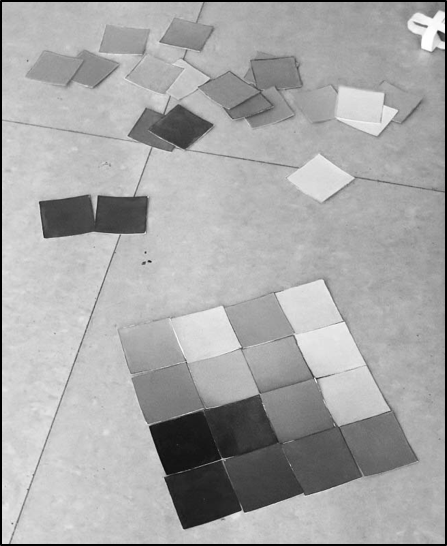

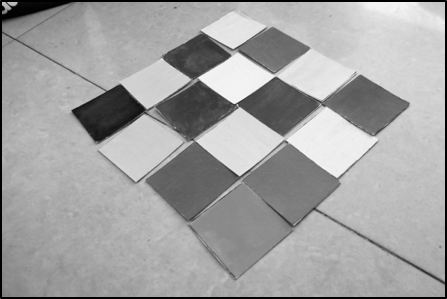

| Template 1: Coloured squares | Participants worked individually to paint a range of coloured squares and group them by tonal value. | Identify coloured squares of similar tonal value and group in larger blocks of 9 or 4 squares to be used in Activities 2 and 3. |  |

| Template 2: Zhabdrung and central axis | Participants worked individually to complete two paintings using this traditional template. | Emphasise tonal values on the template so that the central axis is clearly defined and suitably links the Zhabdrung figure (absent in the template, but the figure’s seat remains) with whatever is above as is seen in Bhutanese thangka. |  |

| Template 3: Changing directional light | Participants worked individually to complete two paintings that used this traditional template. | Change the direction of light within the landscape template so that it reflects a different time in the day suitable for use in the animation profession, for example, where a landscape may have varying directional light sources according to sunset and sunrise. |  |

| Template 4a: Traditional Coloured Squares | The colour palette used in the following Animation activity (4b) was derived from this activity and traditional colours (orange, green, blue and red) used. | Identify coloured squares of similar tonal value and hue, and group in larger blocks of 9 or 4 squares to be used in the Animation activity and to combine at the exhibition. |  |

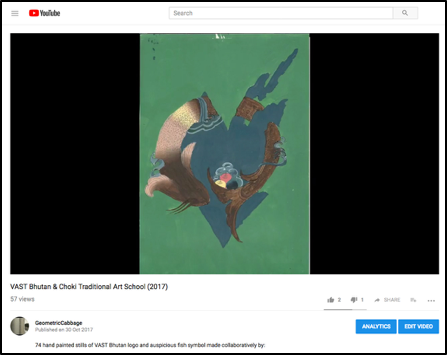

| Template 4b: Traditional Coloured Squares | Participants worked together as a group to paint 74 stills of this template featuring a new composition, the VAST Bhutan logo and the traditional, auspicious fish symbol. In Buddhism, the fish represents good fortune, fertility and abundance as they have the ability to move in water. In each painting, the light moved from within the head to the tail of the fish symbol. | Reflect on learning acquired in Activities 1-3 and cooperating as a whole class, create an animation for an exhibition. |  |

Like the other visual methods used in this research, a ‘critical visual methodology’ was deemed appropriate due to its emphasis on visuals in providing ‘a framework for exploring the almost equally diverse range of methods that scholars working with visual materials can use’ (Rose, 2016, p.24). This methodology evaluates objectives and research sub questions, in four sites:

Within each of these four sites, are three different aspects or modalities:

The ‘social’ is ‘the range of economic, social and political relations, institutions and practices that surround the image and through which it is seen and used’ (Rose, 2016, p.26)

‘Compositionality’ refers to ‘the specific material qualities of an image or ‘visual object’ such as content, colour and spatial organisation’ (Rose, 2016, pp.25-26).

The ‘technological’ refers to ‘any form of apparatus either to be looked at or to enhance natural vision’, such as oil paintings, television and the internet (Rose, 2016, p.25).

By adapting what has already been established, the outcomes produced during the workshop used interpretive narrative which is also customary in thangka practice and Bhutanese popular culture. Interpretive narrative is a form of expression and method of pairing philosophical anecdote and image in Bhutan. This method is popularly practised on social media platforms such as Instagram and Facebook.

Future workshops will explicitly enquire about student expertise and enlist their teaching collaboration, especially in classroom situations that use technologies, such as those used within the animation discipline, of which I have a limited understanding.

Alla prima was developed by sixteenth century Dutch oil painters and used later in the mid-nineteenth century Impressionist movement as seen in the works of French painter Édouard Manet. After the demonstration, students were able to better understand colour harmonisation, evident when comparing their first and subsequent paintings.

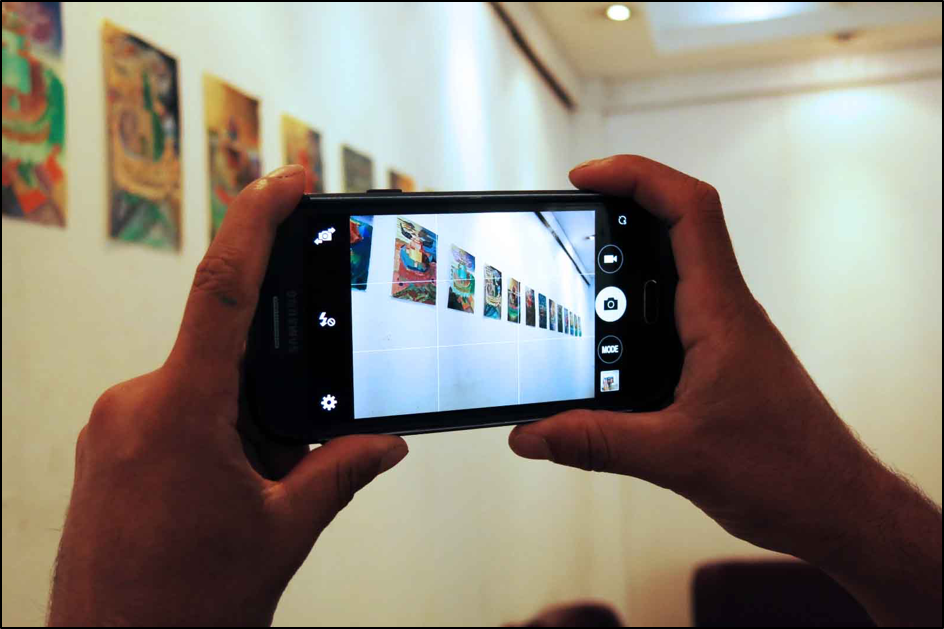

The modular working space allowed participants to engage in other types of viewing experiences and created a ‘sense of awe at the power of an overwhelmingly visual experience’ (Holly in Cheetham, Holly and Moxey, 2005, p.88).

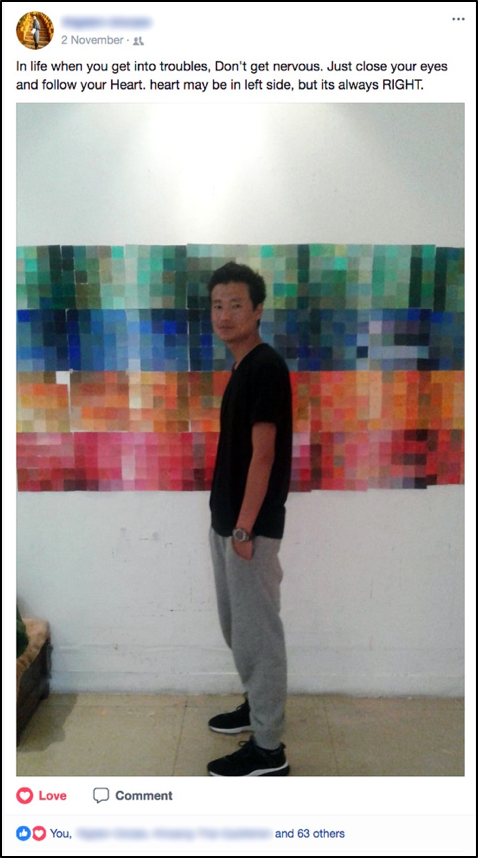

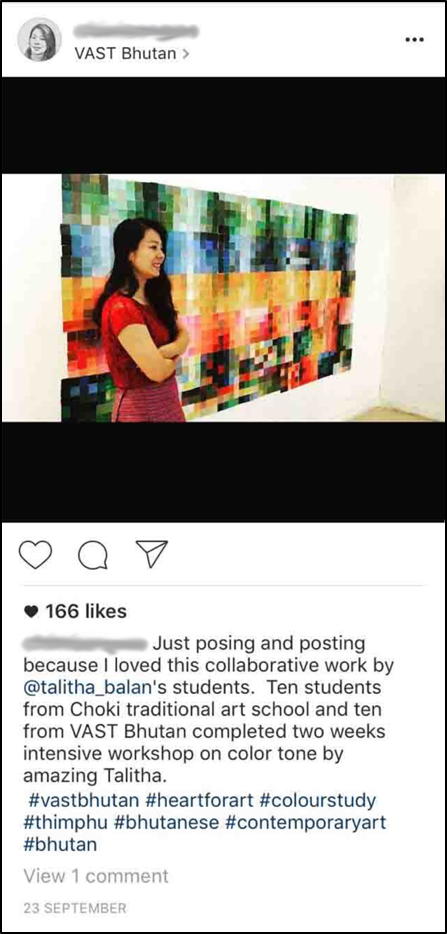

Fortunately, interest generated online was not dependent on knowledge of local events and generated longer lasting effects than the physical display, evident after the exhibition when participants and prominent VAST Bhutan members posted photographs and anecdotes on social media platforms.

Those pictured in front of the Coloured Squares exhibition piece received hundreds of ‘likes’ which are when a Facebook or Instagram account holder indicates that they find the image posted appealing. ‘Likes’ are an indication of those who have at least viewed the piece online.

The Coloured Squares exhibition piece was transformed within the photographic frame and focus on the foreground figure and the background colours harmonizes in-and-out, with the blur effect creating an enhanced awareness of tone and ‘organization of planes’ (Itten, 1970, p.42), further translating on social media platforms.

This article reveals that recent changes affecting traditional Bhutanese painting are the introduction of acrylic paints and the widespread use of online social media platforms such as Facebook and Instagram. Traditional practice is still upheld though these current social media trends suggest adjustments (especially in matters related to colour harmonisation and 3D rendering) could be made within the traditional painting curriculum, without compromising traditional practice, in order to continue engaging young artists and equip them with relevant skills. Project aims are better communicated in visual or photo essay format as it focuses on visual subject matter (i.e. painting) and as workshop outcomes were visual.

Teaching methods were developed to produce a number of culturally specific and non-specific strategies that HE art teachers can use in educational settings populated with students from unknown or mixed cultural backgrounds. The colour study workshop was developed to engage participants to adapt established skills to complexities by encountering unfamiliar ideas using traditional and new technologies. A combination of traditional and non-traditional methods successfully transferred online.

Findings included:

I have been invited back to Bhutan by VAST Bhutan for further work that draws on my expertise. The time leading up to this further visit will be used to refine the workshop methods and future work will likely involve a larger number of participants.

Special thanks to Choki Traditional Art School, VAST Bhutan, Art Matters studio, Meera Curam, Elizabeth Staddon and Nicholas Addison.

Altmann, K. (2016) Fabric of life: Textile arts in Bhutan – culture, tradition and transformation. Berlin: De Gruyter.

Ausubel, D.P. (1968) Educational psychology: A cognitive view. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

Art Mine (2018) History of Acrylic Painting. Available at: https://www.art-mine.com/for-sale/paintings-submedium-acrylic/history-of-acrylic-painting (Accessed: 1 December 2017).

Balan, T (2017) @GeometricCabbage, 30 October, Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cVrOO5H5Hjs (Accessed: 18 August, 2018).

Bartholomew, T.T. and Johnston, J. (eds.) (2008) Dragon’s gift: The sacred arts of Bhutan, Honolulu Academy of Arts. Chicago: Serindia.

Biggs, J. and Tang, C. (2007) ‘Using constructive alignment in outcomes-based teaching and learning’ in Biggs, J.B. and Tang, C. (eds.) Teaching for quality learning at university: What the student does. 3rd edn. Maidenhead: Society for Research into Higher Education and Open University Press, pp.50–63.

Boddy-Evans, M. (2017) ‘Techniques for creating a painting: A look at the various ways or approaches to making a painting’, Thought Co, 1 June. Available at: https://www.thoughtco.com/definition-of-alla-prima-2577452 (Accessed: 16 August 2018).

Cheetham, M.A., Holly, M.A. and Moxey, K. (2005) ‘Visual studies, historiography and aesthetics’, Journal of Visual Culture, 4(1), pp.75-90. https://doi.org/10.1177/1470412905050637.

Choki, S. (2017) Email to Talitha Balan, 7 October.

Choki Traditional Art School (2018) Choki Traditional Art School. Available at: http://www.chokischool.com/ (Accessed: 1 September 2018).

Choki Traditional Art School (2017) Choki Summer Newsletter. Bhutan: Choki Traditional Art School.

Itten, J. (1970) The elements of colour: A treatise on the colour system of Johannes Itten based on his book ‘The Art of Colour’. Translated by van Hagen, E. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold Company.

Karma, N. and Wangdi, K. (2016) DRUK GI LHAZO: The art of Bhutanese painting. Agency for Promotion of Indigenous Crafts, APIC / Ministry of Economic Affairs, MoEA, Royal Government of Bhutan.

McDonald, C. (2004) ‘Ethnography, literature, and art in the work of Anne Eisner (Putnam): Making sense of colonial life in the Ituri Forest’, Research in African Literatures, 35(4), pp.1–16. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/3821200 (Accessed: 14 August 2018).

Orr, S. and McDougall, J. (2014) ‘Enquiry into learning and teaching in arts and creative practice’ in Cleaver, E., Lintern, M. and McLinden, M. (eds.) Teaching and Learning in Higher Education: Disciplinary Approaches to Educational Enquiry. London: Sage, pp.163–177.

Pollock, G. (1988) Vision and difference: Femininity, feminism and the histories of art. London: Routledge.

Rose, G. (2016) Visual methodologies: An introduction to researching with visual methods. 4th edn. London: Sage.

Rigden, D. (2017) Mobile uploads @Rigden Dorjee [Facebook], 2 November. Available at: https://www.facebook.com/photo.php?fbid=161014637822856&set=pb.100017429620629.-2207520000.1535709832.&type=3&theater (Accessed: 1 December 2017).

Rinzin, T. (2017) Profile photo @Yoraj Sharma [Facebook], 4 October. Available at: https://www.facebook.com/photo.php?fbid=755685864616829&set=a.280336552151765&type=3&theater (Accessed: 1 December 2017).

Sharma, Y. (2017) Profile photos #loveart_lovelife_learnlessons_lovevast, @Yoraj Sharma [Facebook], 4 November. Available at: https://www.facebook.com/photo.php?fbid=767978663387549&set=pb.100005262674813.-2207520000.1535709587.&type=3&theater (Accessed: 1 December 2017).

Suchar, C.S. (1997) ‘The physical transformation of metropolitan Chicago: Chicago’s central area’ in Koval, J.P. et al. (eds.) The new Chicago: A social and cultural analysis. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press, pp.56–76.

VAST Bhutan (2017) #vastbhutan #heartforart #colourstudy #contemporaryart @VAST Bhutan [Instagram], 20 September. Available at: https://www.instagram.com/p/BZQYF4LjhkK/?utm_source=ig_share_sheet&igshid=doze5oxt49j1 (Accessed: 1 December 2017).

Voluntary Artist’s Studio Thimphu (2018) VAST, Bhutan. Available at: www.vastbhutan.org.bt (Accessed: 16 August 2018).

Wangchuk, K. (2017) Profile photos @Karma Wangchuk Sonam [Facebook], 25 November. Available at: https://www.facebook.com/photo.php?fbid=10155996432498278&set=a.457224763277&type=3&theater (Accessed: 1 December 2017).

Wilson, R. (1998) ‘A new cosmopolitanism is in the air: Some dialectic twists and turns’ in Cheah. P. and Robbins, B. (eds.) Cosmopolitics: Thinking and feeling beyond the nation. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, pp.351–61.

Zangmo, C. (2017) #vastbhutan #heartforart #colourstudy #thimphu #bhutanese #contemporaryart #bhutan @chimizangmo [Instagram], 23 September. Available at: https://www.instagram.com/p/BZZKN8jgPLp/?utm_source=ig_share_sheet&igshid=ganwlejr3ejs (Accessed: 1 December 2017).

Talitha Balan teaches visual research methods as a Visiting Practitioner for UAL Academic Support and the Central Saint Martin’s Museum and Study Collection. She has completed an MA in Academic Practice in Art, Design and Communication in the Teaching and Learning Exchange at UAL. Artworks created to support her pedagogic and research practices were made during a 2017 artist-in-residence at Art Matters community studio (Richmond Fellowship, UK) and her landscape photomontages have been featured in publications such as Topiaria Helvetica (2015) for the Swiss Society for Garden Culture (SGGK).